I’ve been particularly enjoying thinking more deeply about the books I read and so have given myself the resolution to articulate my thoughts on one book every month. This is my third post in this series of posts on notable works relating to the history of art.

These are my synopses and thoughts on John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. Although the work consists of seven essays, I will not be discussing the three pictorial essays, or the seventh advertising essay. This is therefore the final of three parts.

(Available at: https://www.ways-of-seeing.com/)

For increased readability a pdf containing all three parts is provided here here.

3: “Exceptional work was the result of a prolonged successful struggle”

Synopsis:

Oil painting is not just a technique but an art form, although this was not so until there was a requirement to develop the technique. As an art form they often depict commodities which can be purchased, as well themselves being purchasable commodities. Before anything else, they “are objects which can be bought and owned”.

Oil paint was first used in the 15th century, however, it wasn’t until the 16th that it fully established its own norms, becoming an art form, and although oil paint still continues to be used today the period of the traditional oil painting is roughly set as between 1500 and 1900.

Typically, oil paintings turn every sight into a commodity that can be owned, and contractions like Rembrandt, Vermeer, Turner, etc, are very specific exceptions. The deep contradiction of oil painting stems from the relationship between the tradition of oil painting, and those who are ‘masters’ of it, or the supreme representatives of the craft. The idea of a ‘great artist’ is closely associated with a “man whose life-time is consumed by struggle”, with “every exceptional work being the result of a prolonged successful struggle”.

Art history has not come to terms with the “problem of the relationship between the outstanding work and the average work of European tradition”, there is no recognition of what fundamentally differs these works, and this difference is exemplified more so in oil than any other tradition or culture.

Much art produced after the 17th century was not so meaningful to the painter as finishing his commission and selling his work. “The period of the oil painting corresponds with the rise of the open art market”. This is because the oil painting has an ability to render tangibility and texture, defining “the real as that which you can put your hands on.”

Because of this, despite producing two-dimensional images, oil had a far greater potential of illusionism than sculpture, or, for that matter, any other medium of the time, due to its ability to suggest objects possessing “colour, texture and temperature”.

Earlier art forms, such as medieval or Renaissance religious paintings, depicted wealth as a reflection of divine or hierarchical order—symbolising status ordained by God or tradition. In contrast to this rhetoric, with oil painting emerging alongside capitalism, it symbolically, and overtly, celebrating wealth as fluid, self-made, and driven by a market. Rather than reinforcing a fixed social order, as upheld by feudalism or the church, oil glorified possessions and material success, legitimised not by lineage or divine will, but by the purchasing power of money alone. Of course there is a dichotomy that exists—created by the intersection of commodification and religious depiction.

Of course, if oil paintings depict possessions that can be owned, then the metaphysical implications of objects, like memento mori are limited. How can we depict metaphysical symbols, such as a skull symbolic of death, when it is just a possession that can be owned. The symbol is made “unconvincing or unnatural by the unequivocal, static materialism of the painting-method.”

This is the contradiction which impacts religious paintings of the tradition. They are hypocritical in the regard that everything within the painting is ownable, and takable—undermining their intended spiritual or moral significance. The materiality of oil painting inherently affirms possession and ownership. Even when a painting seeks to depict transcendence, suffering, or divine intervention, the method itself reduces these elements to objects that can be owned and displayed. A painting of the Madonna and Child, while attempting to represent divine grace, is at the same time an object, undermining this. A depiction of Christ’s suffering, while attempting to inspire piety and reflection, exists paradoxically as an object, owned and appreciated not only for its spiritual message but also for its market value.

Thus, oil painting, while capable of illustrating religious themes, struggles to maintain their integrity due to its inherent materialism. The spiritual is rendered into something that is both visually and economically desirable, creating a contradiction between religion and material consumption.

Thoughts:

Early in the chapter Berger discusses the impact of new attitudes to property and exchange, the new power of capital and how the role oil painting took on could not have been found in any other visual art form. I’d first like to elaborate on the context of the sixteenth-century by discussing the “new attitudes to property and exchange” to which Berger refers.

During the early modern period when the shift from feudalism to capitalism was in progress, wealth was increasingly measured in ownable assets rather than inherited land. It was through industrial capitalism that the focus on individual ownership, accumulation, and commodification that art, or in this case, oil painting, became a means by which to display and reinforce the new economic reality.

There is also the question of why oil painting, over any other visual art form, had to portray unique objects in this sixteenth-century. The more accurately a piece could visually embody commodified property and purchasable goods, the closer in value the piece could be argued to be to the actual goods themselves, and thus oil was more appropriate than say, fresco, for visually embodying possessions like jewels, fabrics, and even landscapes or interiors with a level of sensuality that was appreciated by newly capitalist society.

Oil painting, like capital, transformed how value was perceived and understood. Just as capital turned social relations into economic transactions, quantifiable, ownable, and exchangeable, oil painting turned appearances into commodities. Under capitalism, social relations shifted from those based on status and obligation, such as was the case in feudalism, to based on market exchange and private ownership. People increasingly related to one another not through inherited social roles, but through economic transactions—employer and employee, buyer and seller. This commodification of relationships mirrored how oil painting transformed appearances into objects of possession. Through its ability to render textures, surfaces, and light with precision, oil painting made objects seem tangible, possessable, and desirable, reinforcing a worldview with material wealth and ownership at its core.

In keeping with this, Berger argues that art serves both aesthetic and market functions, creating a tension between artistic value and commercial value.

Exceptional works arise when artists push beyond market-driven conventions, engaging more deeply with their role as an artist, or turning technique and tradition against themselves. In contrast, average works conform to market expectations, prioritising saleability over innovation or meaning. This contradiction between art as a medium of expression and as a commodity, begins to explain the divide between truly exceptional art and the more formulaic, commercially driven majority.

At this point my issue with Berger’s views become apparent. Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors from 1533 is, whilst technically masterful, a commission essentially “serving the ideological interest of the ruling class”, and, using what Berger writes in this chapter, you could make the argument this piece is not, in any way, a masterpiece.

Holbein’s piece is quite well recognised to be a masterpiece, however, when examined through Berger’s critique of oil painting I believe you can make the argument that The Ambassadors is not particularly impressive. Berger argues that oil painting mostly serves to glorify material wealth, stating, “What distinguishes oil painting… is its special ability to render the tangibility, the texture, the lustre, the solidity of what it depicts.” This is evident in The Ambassadors, where fabrics, instruments, and material is painted in incredible detail, highlighting and reinforcing the power and status of its subjects, as well as the value of the commodities painted. Berger contends that exceptional works challenge the market-driven nature of art, yet, The Ambassadors remains conventional in its celebration of wealth, aligning with his assertion that “in no other form of society in history has art been so geared to the celebration of wealth.”

Ultimately, The Ambassadors exemplifies Berger’s claim that “oil painting did to appearances what capital did to social relations. It reduced everything to the equality of objects.” While complex and visually striking, the painting does not fundamentally question the values it depicts, instead reinforcing the worldview of the ruling class. By Berger’s standards, it remains conventional rather than truly exceptional. Although, in The Ambassadors, the skull is rendered in anamorphic perspective, appearing warped unless viewed from a specific angle. This separation prevents it from becoming just another tangible possession, preserving its symbolic function as a memento mori, a reminder of mortality that disrupts the painting’s display of power and affluence. Is this enough of a notion to separate the painting from being just another conventional celebration of wealth? One might argue that Holbein subverts oil painting’s typical materialism through the anamorphic skull—introducing an element that actively resists commodification. While the painting celebrates wealth and power, it also confronts the viewer with mortality in a way that disrupts this display. Could this tension place The Ambassadors among the “exceptional works” Berger acknowledges, where an artist’s vision challenges the market-driven conventions of the medium?

Berger suggests that “when metaphysical symbols are introduced, their symbolism is usually made unconvincing or unnatural by the unequivocal, static materialism of the painting-method.” This statement is one that I unequivocally disagree with.

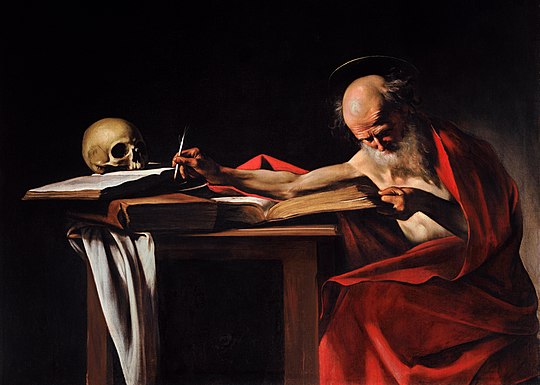

The claim that oil painting’s realism inherently undermines metaphysical symbolism has fundamental issues. Carravagio’s Saint Jerome Writing proves that a skull can be both a physical object and a vanitas symbol, its realism intensifying rather than diminishing its meaning. Caravaggio’s approach demonstrates that oil painting can convey both material presence and deeper philosophical reflection simultaneously—and, personally, creates an incredibly effective memento mori. I could, in fairness, argue that Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro and dramatic composition prevents the skull in Saint Jerome Writing from being reduced to an object. While it is painted with realistic detail, its placement in shadow and its interaction with Jerome’s focus and contemplative state elevate it beyond materialism, maintaining its symbolic power. I might assert that symbolism can survive within oil painting when composition, lighting, and narrative counteract the medium’s inherent materialism, as asserted by Berger.