I’ve been particularly enjoying thinking more deeply about the books I read and so have given myself the resolution to articulate my thoughts on one book every month. This is my second post in this series of posts on notable works relating to the history of art.

These are my synopses and thoughts on John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. Although the work consists of seven essays, I will not be discussing the three pictorial essays, or the seventh advertising essay. This is therefore the second of three parts.

(Available at: https://www.ways-of-seeing.com/)

For increased readability a pdf containing all three parts is provided here here.

3: “To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognised for oneself”

Synopsis:

Men and women have a different kind of social presence. A man’s presence is always (outwardly) directed toward a power which he exercises on others, whereas a woman’s presence expresses her own (inward) attitude to herself. A man’s presence suggests what he is capable of doing to or for others, whereas a woman’s defines what can or cannot be done to her, revealing an asymmetry in perception.

A woman’s self is divided into two distinct parts. She is, alongside herself, “accompanied by her own image of herself”—the surveyor and the surveyed. This surveyor in herself is male, through whom she turns herself into an object—a sight. This internalised male gaze shapes her behaviour and self-perception. Men look at women, and women watch themselves being looked at. This dynamic reinforces the idea that women exist to be observed, while men retain the power to act.

Western artistic tradition reflects this divide. Nude paintings depict a female subject aware of being seen. She is not merely naked—she is presented as an object for the spectator’s gaze. Her nudity is not an expression of self but a performance for an external viewer.

“To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognised for oneself.” A naked body becomes a nude when it is transformed into an object to be seen. In European oil paintings, the nude subject is not the protagonist—this role belongs to the spectator, assumed to be male. Figures are often contorted to be on display to this viewer.

Even when a male lover appears in these paintings, the woman rarely acknowledges him; instead, she continues to engage the spectator. The male lover does not challenge the gaze but rather invites identification, reinforcing the viewer’s authority.

Broadly, the principal protagonist is not depicted; he exists outside the canvas as the clothed spectator, to whom the scene is addressed. This absence, paradoxically, affirms his presence, with the painting’s entire composition structured around his gaze.

Nudity, then, is not so much a state of being being but a form of disguise. The woman is adorned with her own exposure, her nudity crafted to feed an appetite rather than express individuality.

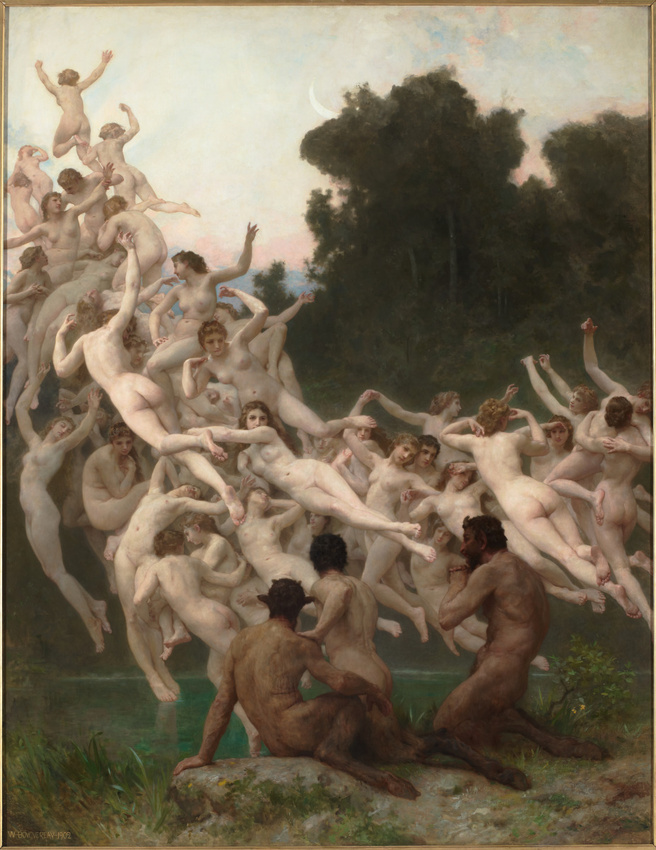

One can observe this reality in nineteenth-century academic art, such as William Bouguereau’s Les Oréades, where nude paintings serve to reaffirm male identity and dominance. They function as a reassurance of male authority, reinforcing traditional gender roles, and reminding men of their position.

The tradition of nudity in European oil painting presents a contradiction. It is often framed as an “admirable expression of the European humanist spirit,” a celebration of individualism. Yet, while the artist asserts his own subjectivity, the female figure is denied hers—she exists solely as an aesthetic object.

This structure persists in the consciousness of many women. As a result, they do to themselves what men do to them: they survey their own femininity. The internalised male gaze ensures that women continue to monitor their appearance, preemptively shaping themselves to fit external expectations.

Women are depicted differently from men, not due to inherent differences in masculinity and femininity, but because the ‘ideal’ spectator is always assumed to be male. This assumption not only dictates how women are represented but also conditions how they present themselves in society.

Thoughts:

One consideration I would like to make is for the tradition of the nude in European oil painting as a contradiction. I would argue Renaissance and post-Renaissance humanism is one of the key ideals placed under scrutiny in Berger’s third essay.

Humanism, in this historical context, describes the intellectual movement that emerged during the Renaissance which emphasises the value, beauty, and dignity of humans. The movement focused on individual potential, classical antiquity, and rational understanding. Directly translating these ideals into art led to a revival of idealising representations of the human form, inspired by Greco-Roman sculpture, in which the nude had become a symbol of beauty, knowledge, and philosophical ideals.

I interpreted Berger’s argument as suggesting this humanist approach was often a guise for a more objectifying and possessive gaze. It can be interpreted that the European tradition of the nude in oil painting, while framed as a celebration of humanist ideals, was in practice deeply tied to male spectatorship, where the female body was displayed for the pleasure of a male viewer rather than as an autonomous subject in her own right.

In this regard, the humanist spirit Berger mentions is both an ideological justification for the tradition of nude painting and, almost paradoxically, a framework that enabled the continued objectification of women as the embodiment of artistic ideals in contemporary culture.

Despite this, I’d broadly like to focus my analysis on nineteenth-century academic art. In Ways of Seeing, Berger argues that these paintings functioned as tools of patriarchal reinforcement in male-dominated spaces like state and business. The quote—“Men of state, of business, discussed under paintings like this. When one of them felt he had been outwitted, he looked up for consolation. What he saw reminded him that he was a man”—highlights how such art reaffirmed male identity and dominance.

The nude female figure, objectified and passive, contrasted with the active, clothed male spectator, who derived a sense of authority from his position as the “ideal viewer.” This dynamic directly reflected societal norms where men occupied public decision-making positions, while women were relegated to aestheticised roles. It is not difficult to argue that this persists in contemporary culture. In her 1988 piece Vision and Difference, Griselda Pollock highlights that nineteenth-century bourgeois spaces, such as government offices and boardrooms, often displayed nudes to symbolise male control over both art and society—directly supporting and elaborating on Berger’s statement. These images served to reinforce the exclusion of women from power. (source (1)) Similarly, Carol Duncan’s 1993 The Aesthetics of Power argues that such art normalised the idea that women existed for male consumption, both visually and socially, providing objectification that would further pacify women. (source (2))

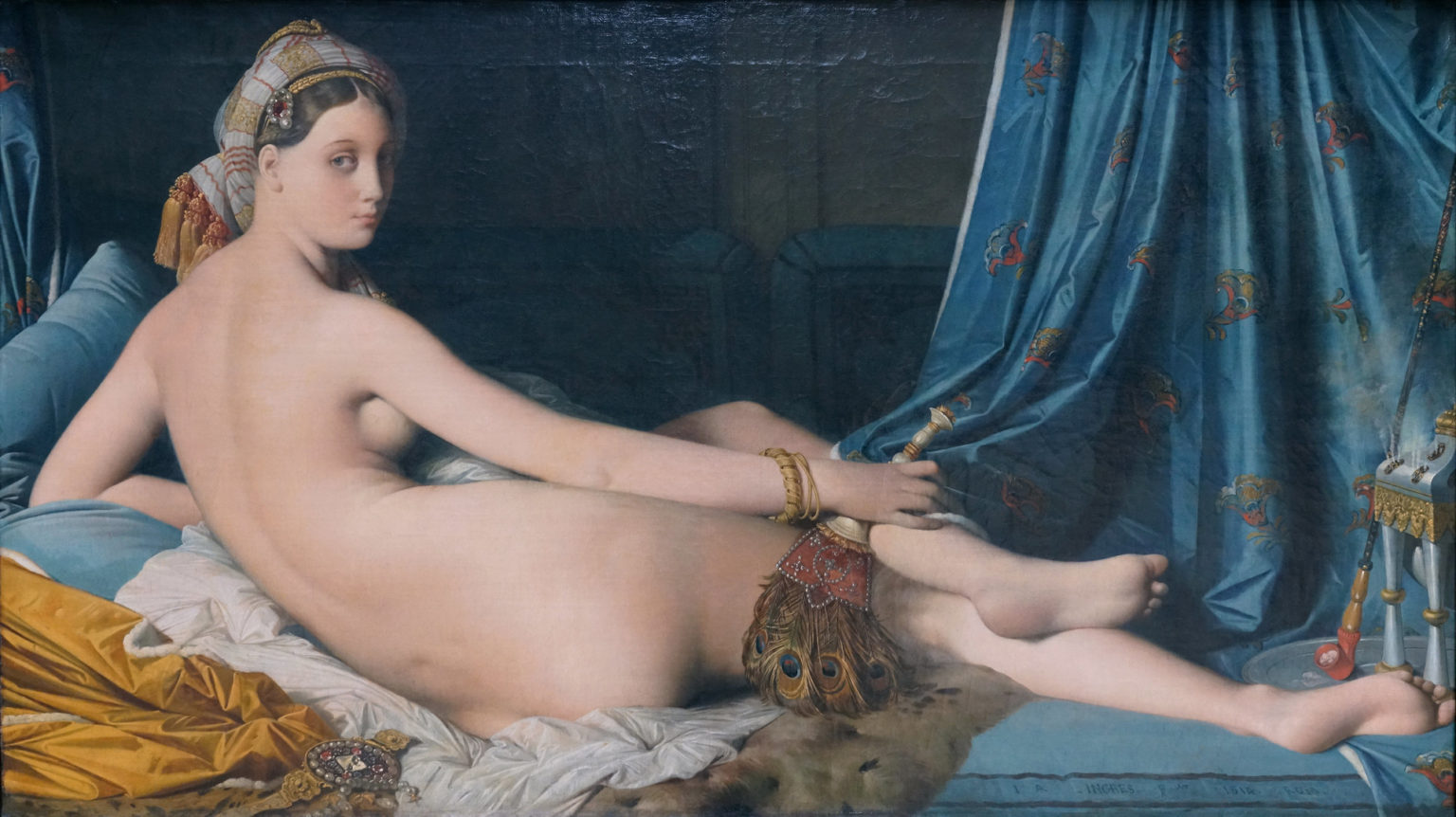

In part this illustrates how historically objectification of women in art paralleled their marginalisation in public life—a visual culture perpetuating systemic gender biases. The nineteenth-century “cult of the nude” normalised women’s absence from serious intellectual or political discourse, framing them as decorative rather than functional. (source (3)) Representation in art such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ 1814 La Grande Odalisque, reinforced the notion that women lacked the rationality or authority required for state and business roles. (source (4)) Depicting a reclining nude woman in an exoticised, Orientalist setting, with her elongated body and passive pose emphasising her role as an object of male desire rather than an active subject. Often Ingres’ work reflected the nineteenth-century fascination with the female body as an object of aesthetic and erotic pleasure. The odalisque’s lack of agency and her positioning as a decorative figure reinforce the idea that women exist for visual consumption, not intellectual or political engagement.

Contemporary underrepresentation stems, at least in part, from these nineteenth-century norms, men are associated with “agency” and women with “passivity”—forming modern barriers in leadership. (source (5))

This analysis reveals how nineteenth-century art played a part in naturalising male dominance in public spheres. By positioning women as passive objects for visual consumption, these “cult of the nude” works not only reinforced gendered power imbalances in the nineteenth century but also acted as foundational templates for contemporary media representations, where remnants of this patriarchal gaze continue to inform societal norms. It is in this vein that historical visual culture contributed to systemic gender biases that persist today, and although they exist in largely different forms, there are stark similarities.

(1) Pollock, G. (1988). Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism, and Histories of Art. Available at: https://archive.org/details/vision-and-difference-by-griselda-pollock/page/n51/mode/2up (Accessed: 16 February 2025)

(2) Duncan, C. (1993). The Aesthetics of Power: Essays in Critical Art History. Available at: https://archive.org/details/aestheticsofpowe0000dunc/mode/2up (Accessed: 16 February 2025)

(3) Markowitz, S., Solomon-Godeau, A., Cohan, S. (2001). Male Trouble: A Crisis in Representation. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 324327819_Male_Trouble_A_Crisis_in_Representation (Accessed: 16 February 2025)

(4) Painting Colonial Culture: Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque. Available at: https://smarthistory.org/painting-colonial-culture-ingress-la-grande-odalisque/ (Accessed: 16 February 2025)

(5) Eagly, A. H., Carli, L L. (2007). Through the Labyrinth: The Truth about How Women Become Leaders. (Available at the British Library but apparently nowhere online)