I’ve been particularly enjoying thinking more deeply about the books I read and so have given myself the resolution to articulate my thoughts on one book every month. This is my first post in this series of posts on notable works relating to the history of art.

These are my synopses and thoughts on John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. Although the work consists of seven essays, I will not be discussing the three pictorial essays, or the seventh advertising essay. This is therefore the first of three parts.

(Available at: https://www.ways-of-seeing.com/)

For increased readability a pdf containing all three parts is provided here here.

1: “If we can see the present clearly enough, we shall ask the right questions of the past”

Berger’s first essay is itself based on The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction by Walter Benjamin. (Available at: https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/benjamin.pdf)

Synopsis:

Seeing is the purest most fundamental way to experience. However, how we see is affected by what we believe.

Whilst we see, we are also seen, and this “reciprocal nature of vision” is more fundamental to seeing than to speaking—we use dialogue to verbalise how we see, and to ascertain how others see.

An image embodies a “way of seeing”, for example, a painter’s “way of seeing” is reflected in how they mark the canvas to produce their image. The more imaginative a work, the more it tells us about the artist’s experience and perceptions.

The vision of the image-maker was not always considered part of the recorded image, however, since the Renaissance period an image has become a record of how X saw Y. This stems from an increasing “consciousness of individuality” and growing “awareness of history”.

Our perception of an image depends on our own way of seeing, as well as our assumptions about beauty, form, taste, and civilisation. These assumptions obscure the past, which is a “well of conclusions from which we draw in order to act”. Mystification of the past leads to works of art becoming “unnecessarily remote” and a lesser ability to draw conclusions from the past. Mystification is the process of explaining away what might otherwise be evident.

History constitutes the relation between a present and past. The fact that comparison can still be made indicates that “we still live in a society of comparable social relations and moral values”. “If we can see the present clearly enough, we shall ask the right questions of the past.”

From our position in the present we perceive art in a different way. During the Renaissance the convention of perspective was centered on the eye of the beholder. “The visible world is arranged for the spectator as the universe was once thought to be arranged for God.”

The camera destroyed the idea that images were timeless. “The uniqueness of every painting was once part of the uniqueness of the place where it resided”. However, with the advent of photographic reproduction, and television, a single image “enters a million other houses and, in each of them, is seen in a different context.”, and so, “the uniqueness of the original now lies in it being the original of a reproduction.”

This shift also transformed how the meaning of a work is understood. “The meaning of the original work no longer lies in what it uniquely says but in what it uniquely is.”. “It is authentic and therefore it is beautiful.”

Thoughts:

I interpreted the first portion of this essay as suggesting that sight is the most fundamental way to experience, in the sense that, as a way to experience, seeing is the fullest way to experience reality—not the most accurate. In fact we must reconcile what we see to happen and what we know to happen.

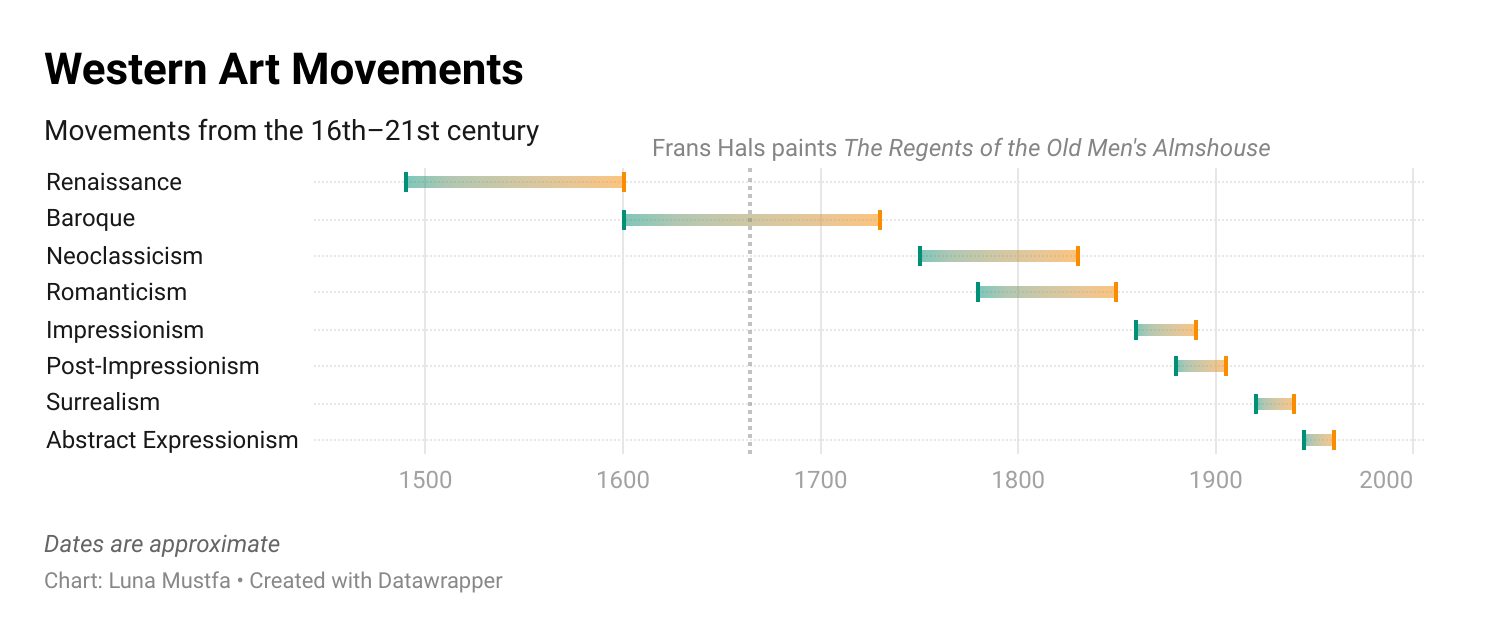

The idea that our own way of seeing impacts our perceptions is hard to disagree with, although, I think, broadly overlooked. The contextual lens through which we see art is evermore relevant—as we move increasingly further from the time of, to use Berger’s own example Frans Hals’, The Regents of the Old Men’s Almshouse. (source (1))

Analysis of paintings deals in fact, often focusing on the life of the artist, in an effort to provide much needed historical context. The most interpretive analysis touches on potential symbolic meaning—but never on how the piece should make you feel. There is no objective analysis on the emotional impact of art. This is no mistake as, after all, our own “way of seeing” is deeply impactful to how we understand art.

Herein lies the issue. We reside in the present, and our experiences in this present shape our way of seeing. We bring this present “way of seeing” with us even as we attempt to position ourselves in the past and experience works like The Regents of the Old Men’s Almshouse in their most original capacity. An example particularly supportive of this issue is Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights. (source (2)) This work is widely accepted to be a moral and religious allegory, but today no one could be blamed for seeing an erotic and hedonistic piece with its abundant nudity and scenes of indulgence, a celebration of sensuality rather than the condemnation of sin that late-mediaeval Christian theologians would have seen.

This modern impression; a more secular, hedonistic reading is a result of mystification from Dalíesque imagery, reframing the painting as an exploration of the subconscious and distancing itself from its religious roots. This combined with a lack of familiarity with the symbolic language of mediaeval christianity masks a late 15th century understanding.

Berger’s statement “History always constitutes the relation between a present and its past” drew me to consider the importance of the ever-present effect of applying our own modern assumptions about beauty, form, taste, and society.

There is a credible abstraction from building upon the idea that “we still live in a society of comparable social relations and moral values”. In the words of Isaiah Berlin, “to foresee the future is to confuse the future with the present”. In the future will there be comparable social relations and moral values? Already there is a disconnect between past and present—how this disconnect grows will impact how future generations interpret art, but is this actually a problem?

Contemporary analysts might suggest that increasing historical and cultural difference enriches interpretation. Berger himself stated that “today we see the art of the past as nobody saw it before. We actually perceive it in a different way.” However, he might also argue that as time passes the chance for mystification to occur grows. Berger explains mystification as a mechanism by which evident truths are deliberately obscured to serve ideological or institutional interests. Mystification reframes what could be understood through direct experience or historical context into abstract terms, alienating the observer and assigning the interpretive authority to a select few. By detaching art from its historical context, for example, in the case of The Regents of the Old Men’s Almshouse, the economic or social context of a work’s creation, mystification upholds existing power structures and diminishes a viewer’s capacity for personal interpretation. This idea reinforces the necessity of demystifying art to allow individuals to more deeply connect with it without the mystification of institutionalised narratives.

Whilst I can argue for this point, I think there is an almost conspiratorial angle to the idea. In the last century alone, significant social-political ideological changes have altered the lens through which we view art. This can be illustrated when discussing the feminist movement’s impact on Titian’s 1538 commission Venus of Urbino. (source (3))

Venus of Urbino was likely commissioned as a celebration of marriage, love, and fertility. The reclining figure of Venus in a context that emphasised her beauty and sensuality—symbols of idealised femininity as well as her direct gaze and the intimate domestic setting articulate notions of marital intimacy and wifely virtues.

During the 1970s and 80s critique of patriarchal constructs in art began to emerge—Charles Hope directly discussed Venus of Urbino and Titian’s similar works noting that they often portrayed women as passive subjects, aligning with societal structures that objectified women for visual consumption. (source (4))

Laura Mulvey’s 1975 essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (which developed the concept of the “male gaze”) provides a framework for analysing how visual arts position women as objects for male viewers and while Mulvey originally addressed film, her principles have often been applied to paintings, including Venus of Urbino. (source (5)) Increasingly reinterpreted as a reflection of patriarchal norms, where the female body is idealised as a commodity for a male audience, the reclining nude in Venus of Urbino now reflects an archetype of women positioned as objects within an androcentric artistic sphere. The direct gaze of Venus, a focal point for critique, can be interpreted as reinforcing the (assumedly male) observer’s role as the subject controlling the narrative.

Therefore, whilst originally perhaps a celebration of marital sensuality, today Venus of Urbino might be critiqued as a representation of patriarchal beauty standards or even, somewhat alternatively, celebrated as a reclamation of female agency, depending entirely on the lens used.

In the way that the lens (or “way of seeing”) of the observer changes how the work is perceived Berger’s suggestion that the words surrounding reproductions of painting change the image has, to me, much credibility after my visit to Sir John Soane’s Museum—which lacks labels or panels, allowing a visitor to draw their own inspiration from the museum. (source (6))

My final thought on Berger’s first essay is related to his position on the uniqueness of original works of art. I do understand and, in part, agree with the sentiment that most people experiencing (original) paintings have seen the piece before, and as such the painting is reframed as an “original of a reproduction”.

The idea that seeing a painting for the first time has fundamentally changed is, to me, best exemplified in Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Whilst the work exists as an original in the Louvre, its cultural significance has been largely transformed by reproductions of this original. Most people who know the Mona Lisa have encountered it in digital images, books, or, perhaps, novelty t-shirts and mugs. These reproductions maintain their own meanings—entirely removed from the context of the 16th century. Through these reproductions the Mona Lisa has become less of an Italian Renaissance masterpiece and more of a generic symbol of classical art, commodified and removed of its historical context.

When viewing any original work in person, the experience is affected by our own “way of seeing”. The original no longer exists as a purely unique work; instead acting as a reference point for its reproductions. This reframing aligns with Berger’s argument that, in modernity, the value of an “original” is shaped as much by its physical presence as by the nature of its originality (and market value!).

(1) The Regents of the Old Men’s Almshouse (Accessed: 22 January 2025)

(2) The Garden of Earthly Delights (Accessed: 22 January 2025)

(3) Venus of Urbino (Accessed: 22 January 2025

(4) Hope, C. (1980). Problems of Interpretation in Titian’s erotic Paintings. Tiziano e Venezia. (Available in the Warburg Institute Library but apparently nowhere online)

(5) Miller, M. M. (2021). Titian’s Venus of Urbino: A Comprehensive Art Historical Study with an Interpretive Consideration. Available at: link (Accessed: 22 January 2025)

(6) Willkens, D.S. (2016) Reading Words and Images in the Description(s) of Sir John Soane’s Museum. Architectural Histories, 4(1), p.5. Available at: link (Accessed 22 January 2025)